Building a better whooping cough vaccine

Breaking down whooping cough infections

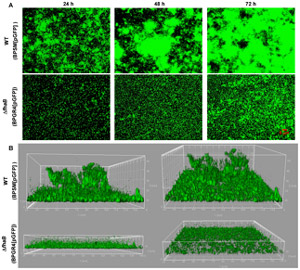

By Victoria MartinezBiofilms produced by mutant and regular strains ofBordetella pertussis doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028811.g003

Like many infectious diseases, whooping cough is extremely hard to treat, but scientists using the Canadian Light Source may have found a new way to treat and vaccinate for this deadly disease.

The bacteria that cause whooping cough form a protective biofilm inside the people it infects, making it incredibly resistant to treatment.

A team of researchers from The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), the University of Toronto, and the Wake Forest School of Medicine have identified a protein that allows these bacteria to form a protective biofilm, pointing the way to new treatments and vaccine options for both whooping cough (Bordetella pertussis) and its animal-infecting cousin, kennel cough (Bordetella bronchiseptica).

The original whooping cough vaccine was phased out in the 1990s, as families became concerned about the extreme side effects of the whole-bacteria treatment. A newer vaccine which only uses part of the pertussis bacteria exists, but is nowhere near as effective as the older treatment.

“With the new vaccine, older children and adults that still carry the pertussis bacteria in their nose ultimately end up transmitting the bacteria to non- or under-immunized infants,” explains Dr. Rajendar Deora, Wake Forest School of Medicine team lead. “For young children, an infection can sometimes be lethal.”

Deora’s lab found that bacteria lacking a specific protein, BpsB, keeps producing long sugar chains but couldn’t use them to form hardy biofilms.

In order to harness this change, Deora’s team took a closer look at BpsB’s protein structure with the help of researchers from Dr. Lynne Howell’s SickKids’ lab and CLS crystallography facilities.

“If you know the structure of the protein machinery in the system, then you could rationally design a small molecule or drug to block or target that function,” explains structural biologist Dr. Dustin Little, a member of Howell’s team and lead author on their most recent paper on B. bronchisepticaBpsB protein.

“Ultimately, we can think of breaking up or disrupting the biofilms by treating BpsB with a molecule or drug,” says Deora.

Already, the team is looking at ways to test these new structural and functional insights in vitro, as a first step towards treatment application. Theoretically, the same tools that block the formation of new infectious biofilms should also help break down existing biofilms, and vastly reducing whooping cough’s ability to infect new individuals.

Little, Dustin J., Sonja Milek, Natalie C. Bamford, Tridib Ganguly, Benjamin R. DiFrancesco, Mark Nitz, Rajendar Deora, and P. Lynne Howell. "BpsB is a Poly-β-1, 6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine Deacetylase Required for Biofilm Formation in Bordetella bronchiseptica." Journal of Biological Chemistry (2015): jbc-M115.

About the Canadian Light Source Inc.:

The CLS is the brightest light in Canada—millions of times brighter than even the sun—used by scientists to get incredibly detailed information about the structural and chemical properties of materials at the molecular level, with work ranging from mine tailing remediation to cancer research and cutting-edge materials development.

The CLS has hosted over 2,500 researchers from academic institutions, government, and industry from 10 provinces and 2 territories; delivered over 40,000 experimental shifts; received over 10,000 user visits; and provided a scientific service critical in over 1,500 scientific publications, since beginning operations in 2005. The CLS has over 200 full-time employees.

CLS operations are funded by Canada Foundation for Innovation, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, Western Economic Diversification Canada, National Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Government of Saskatchewan and the University of Saskatchewan.

For more information visit the CLS website or contact:

Victoria Martinez

Communications Coordinator

1 (306) 657-3771

victoria.martinez@lightsource.ca