Protecting our food from mercury contamination

One size does not fit all when it comes to using biochar for soil remediation, according to researchers who used the CLS.

By Greg BaskyTwo men river fishing.

Mercury is used in a variety of industries, including textile manufacturing and gold and silver mining. When released into the environment, this highly toxic element causes widespread contamination of soil. As mercury enters rivers, lakes and oceans, it is converted to methylmercury, a neurotoxin that moves into the food chain through fish and seafood, posing a serious risk to human health.

Conventional methods of remediating mercury-contaminated soil – such as adding activated carbon – can be quite expensive to apply on a large scale. However, recent research has found that biochar, a charcoal produced by superheating agriculture or forestry waste in the absence of oxygen, holds promise as a low cost, “green” alternative.

Most studies to date have focused on biochar’s ability to control the release of mercury and production of methylmercury from waterlogged soils. A team of researchers from the University of Waterloo recently set out to determine how effective biochar is at amending soils that see frequent drying and rewetting, such as floodplains.

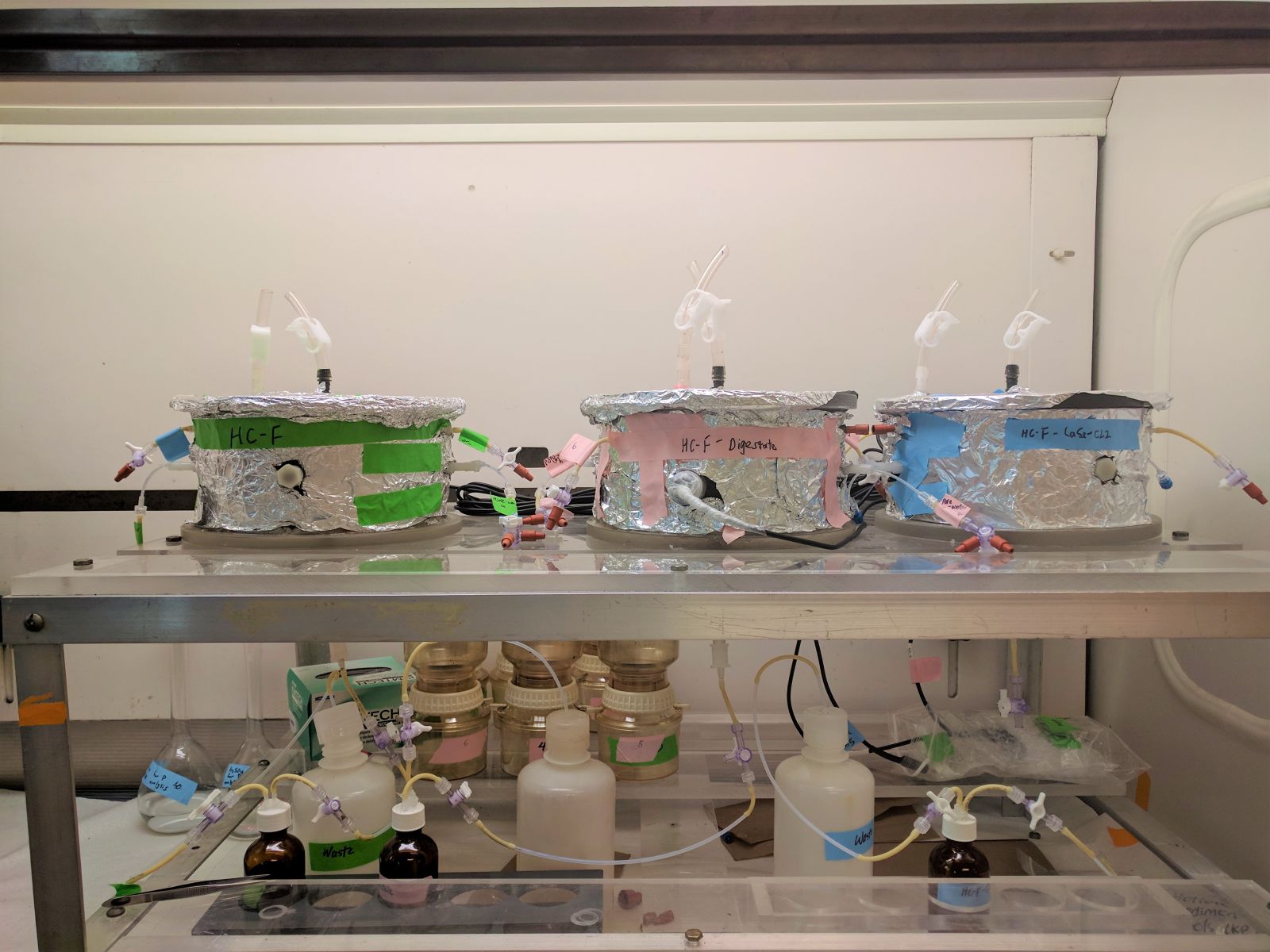

PhD student Alana Wang and colleagues added two types of biochars – sulfurized wood and anaerobic digestate – to soil samples drawn from floodplains along Virginia’s South River. A chemical plant in Waynseboro, VA disposed of mercury waste in that river from 1929 to 1950.

Each soil sample was subjected to 10 cycles of wetting with river water and drying with repeated testing throughout. The research team was surprised to find that, early on in the study, the biochar-amended soil actually released higher levels of mercury.

“Our previous studies demonstrated that the addition of sulfurized hardwood biochar was very effective for removing mercury from aqueous solution under both stagnant and saturated-flowing conditions,” said Dr. Carol Ptacek, a member of the research team. As the wetting and drying cycles continued though, the biochar-treated soil released less mercury and had lower concentrations of methylmercury – more in keeping with what they had expected to find, based on other studies.

Wang and Ptacek believe the higher levels of mercury and methylmercury they initially observed were a result of the soil being dried before the start of the experiment – similar to what might occur after a lengthy drought.

The researchers used the SXRMB beamline at the CLS to analyze sulfur in the solid materials they collected during their research. The synchrotron enabled the team to detect changes in the sulfur chemistry, which suggests sulfurized biochar is prone to oxidization after repeated wetting and drying. These chemical changes have the potential to cause other environmental problems such as turning the water acidic. “The results of the sulfur analyses at the CLS provided important information on how drying and wetting affected sulfur chemistry in the amended systems,” said Wang.

“Our group’s work benefited tremendously from the application of a variety of synchrotron techniques,” added Ptacek.

The team concluded that repeated drying and wetting can affect the ability of biochars to stabilize mercury in soil and published their findings in Chemosphere. “We found out that soil remediation does not have a one-size fits all solution,” said Wang.

It turns out that remediation projects likely need customized materials to add to the soil, based on the specific soil characteristics and conditions in a given area. “Some materials may work under certain conditions, but they might not work under all conditions. When developing plans for field-scale projects, simply focusing on what material to use may not be enough. Environmental conditions and how materials respond to different environmental conditions may also be important,” added Wang.

Wang, Alana O., Carol J. Ptacek, E. Erin Mack, and David W. Blowes. "Impact of multiple drying and rewetting events on biochar amendments for Hg stabilization in floodplain soil from South River, VA." Chemosphere 262 (2020): 127794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127794

For more information, contact:

Victoria Schramm

Communications Coordinator

Canadian Light Source

306-657-3516

victoria.schramm@lightsource.ca